Last year I joined a biweekly book club – organized by MCC alumni Mike Roberts – where each member leads a meeting by sharing on a book that they’ve found interesting or insightful.

Recently I shared on The Upswing by Robert Putnam and Shaylyn Romney Garrett. The central thesis of The Upswing begins by arguing that America’s Gilded Age – 1870s through 1890s – is remarkably similar to our current times.

“Inequality, political polarization, social dislocation, and cultural narcissism prevailed — all accompanied, as they are now, by unprecedented technological advances, prosperity, and material well-being.”

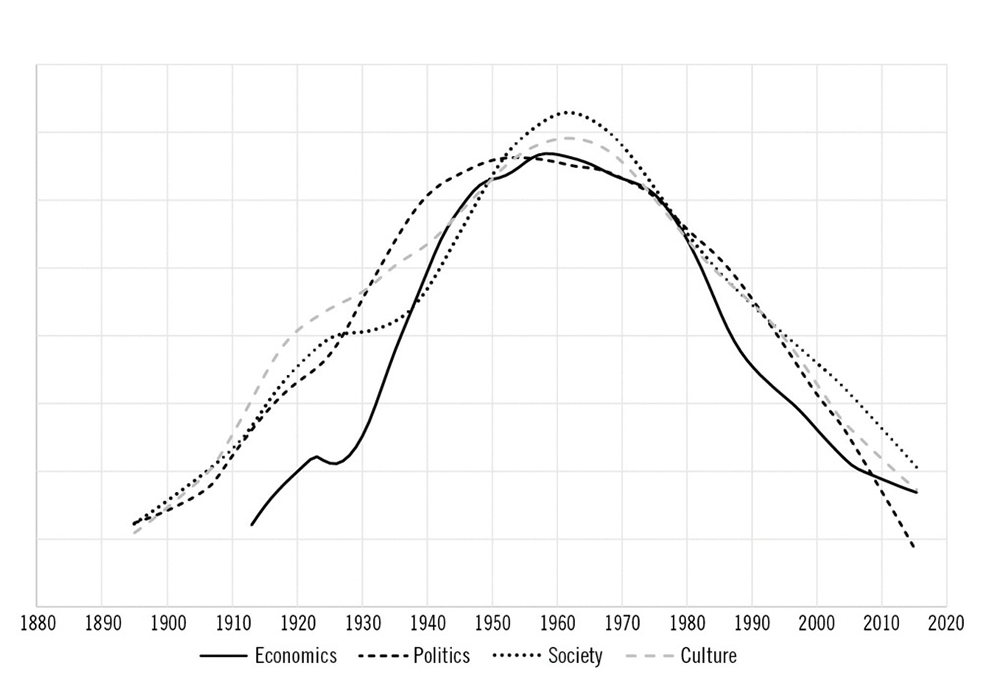

The authors then introduce the inverse U graph, which they label the “I-we-I” trend, that served as the inspiration for this book. Putnam repeatedly came across this trend while analyzing historical data sources across economics, politics, civil society, and culture. This trend can even be seen in data ranging from deaths of despair to cross party voting.

This chart above graphs the aggregate data to show visually how equality in the US grew from the low point of the 1890s – with a brief disruption during the 1920s – to its steady progress towards equality from the 1930s to 1960s before beginning to decline until reaching its current point.

It’s a fascinating, dense, and data grounded book. The main text is followed by around a hundred pages of citations. It presents a rich and cohesive perspective that at times diverges in unexpected ways from the common narratives about American society.

The reason I’m writing about The Upswing here is because I wanted to share some of my learnings from one section of Chapter 4: Society – Between Isolation and Solidarity. This Chapter is divided into four sub-sections following the most critical social groups identified by the authors: Civic Associations, Religious Groups, Labor Unions, and Family Formation.

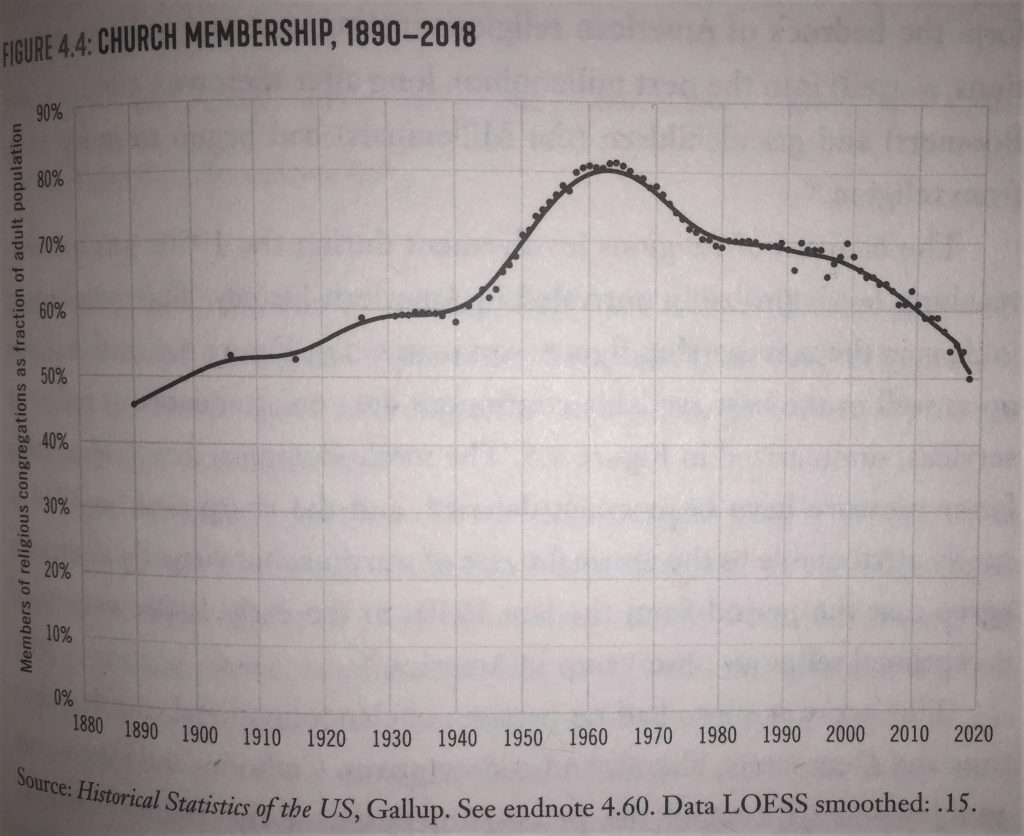

The sub-section that I want to share about here – perhaps not too surprisingly – was the subsection on Religious Groups. There’s been a growing narrative – driven by falling membership and attendance numbers, as well as rising rates of people claiming no religious affiliation – that the American Church is facing inevitable decline. As the same time, the surge of Christian nationalism and legalism can be seen as a…in my opinion deeply misguided…backlash to this trend of decline. The authors do not dispute the decline of the Church in America – in fact they present significant data on the decline – but they put this decline within a historic framework that, at least from my perspective, dramatically recontextualizes it.

The last time American society looked like it does today – massive wealth inequality, political deadlock, cultural narcissism, partisan division, broken communities, expanding poverty, rapid technological growth – Church membership and attendance had also collapsed. The authors note that, “like contemporary religious ‘nones’, those who profess no religious identity, these secular Americans were not necessarily unbelievers, but they were unattached to religious institutions by membership, attendance, or contributions.” One notable historian of American religion, Sydney Ahlstrom, reported that only 43% of the total American population claimed any church affiliation in 1910, compared to 45% in 2023 (that’s membership, not active involvement). A 1909 Washington Post article estimated that the unchurched population “probably outnumbers our church members in proportion of about three to two.”

The authors add that, “with increasing immigration from Catholic countries, religion was becoming a sectarian, divisive force, even provoking anti-Catholic violence along the Eastern seaboard. Nativist, ethnocentric, anti-Semitic, and racist sentiments were common, often entangled with religious intolerance.” The specific issues driving polarization, strife, and division in the Church were different but the result was the same as in recent decades.

Not only have the working class become alienated from the churches, especially from the Protestant churches, but a very large proportion of the well-to-do men and women who belong to the so-called cultured class have lost touch with church work. Some retain a membership, but the church plays no vital or important part in their lives… And what is more this indifferentism is by no means confided to the “wicked city” but prevails throughout the country in small towns and villages as well as in large cities – except possibly in a few localities where “revivals” have recently stirred the people.

Ray Stannard Banker, 1910

During the Gilded Age, the authors write that Protestant theology largely focused on personal piety and individual salvation.

Concentrating on the individual sinner led inexorably to a preoccupation with exceedingly personal sins. The resultant erosion of social ethics was noted even in colonial times, but the full effect of this tendency did not manifest until after the Civil War, when the rise of huge corporate entities began to complicate the moral life of nearly all Americans. Revivalism tended to become socially trivial or ambiguous to the point of irrelevance.

Ahlstrom, Religious History of the American People, 844

Secular society at the time was also focused on individualism with a strong embrace of “social Darwinism” among the intellectual class and upper middle class. As American sociologist William Graham Sumner wrote at the time, inspired by Herbert Spencer, “some people were better at the contest of life than others… The good ones climbed out of the jungle of savagery and passed their talents on to their offspring, who climbed still higher… Attempts to overrule evolution – as by alleviating the plight of the poor – were both immoral and imprudent.” This line of thinking lead to scientific racism, eugenics, and a pseudo-biological defense of laissez-faire capitalism. I think we can hear echoes of it today among Silicon Valley elites who idolize Ayn Rand and advocate for dismantling democracy in favor of meritocracy (where merit is determined by them, of course).

So if the Church in America was in a similar state a century ago – facing increasing fragmentation and declining engagement, with even revivals losing their efficacy – the driving question is what changed?

The answer from the authors is actually surprisingly straightforward, “mainline Protestants began to pivot from individualism toward concern with the broader community, best exemplified by the Social Gospel movement, an effort by Liberal Protestant leaders to bring pressing social problems such as urban poverty to the attention of their middle-class parishioners and to highlight the importance of social solidarity over individualism.” This movement was focused on long term community involvement – not one time service projects or political advocacy – with Churches across the country opening themselves up to the community and becoming what religious historic E. Brooks Holifield termed “social congregations.”

Thousands of congregations transformed themselves into centers that not only were open for worship but also available for Sunday school, concerts, church socials, women’s meetings, youth groups, girl’s guilds, boy’s brigades, sewing circles, benevolent societies, day schools, temperance societies, athletic clubs, scout troops, and nameless other activities… Henry Ward Beecher advised the seminarians at Yale to “multiply picnics” in their parishes, and many congregations of every variety proceeded beyond picnics to gymnasiums, parish houses, camps, baseball teams, and military drill groups.

E. Brooks Holifield, Toward American Congregations, 39-41

It was in this era that the phrase “What would Jesus Do” was popularized in a best-selling 1899 novel by Charles Sheldon to advocate for the Social Gospel and that Christians live out the Beatitudes in their communities. Not all American Christians agreed with this shift towards a “Social Gospel” and the authors note that this period is when many churches joined the Fundamentalist movement (which would later lead to contemporary Evangelicalism) and split away from mainline Protestantism in the United States.

The Church’s deepening engagement with the broader community lead not only to growth but also to broader social change and political reform. This movement was often “bottom-up” with changes occurring on the local level first but, as the Church is a cross-cut of society, the authors note that members of the Upper Class – like Frances Perkins – were inspired by the Social Gospel and moved from community level work to State or National level reform.

I think another important question to address is why does active church attendance matter? As Christians, we have our own priorities and perspectives that frame our answer to this, but the authors answer this from their perspective at the beginning of the section on religious groups.

Religious institutions have long been the single most important source of community connectedness and social solidarity in America. Even in our secular age, roughly half of all group memberships are religious in nature – congregations, Bible study groups, prayer circles, and so forth – and roughly half of all philanthropy and volunteering is carried out in a religious context. For many Americans religion is less a matter of theological commitment than a rich source of community. And involvement in a faith community turns out to be a strong predictor of connection to the wider, secular world.

Active members of religious congregations are more likely than secular Americans to give generously to charity, and not merely in the offering plate, but also to secular causes. Regular churchgoers are more than twice as likely to volunteer as demographically matched Americans who rarely attend church, and to volunteer not merely for church ushering, but also for secular causes. Religious Americans are two or three times more likely than matched secular Americans to belong to secular organizations, like neighborhood associations, Rotary, or the Scouts, and to be active in local civic life. Rigorous statistical analysis suggests (surprisingly, perhaps, to secular Americans) that the link between religious involvement and civic do-gooding is not spurious, but probably causal. In short, trends in religious engagement are key indicators of trends in social connection more generally.

The Upswing, pg. 127-128

As you can probably tell, considering how much I’ve written just on one sub-section of one chapter, this book is overflowing with information. It’s hard to fight the temptation to share one more thing and then another thing. Especially on the other side of the trends where the authors identify the mid-1960s to the early 1970s as the period where the titular “Upswing” stalled out leading to decades of declines across most indicators – including Church engagement. There’s a long, multifaceted answer provided in The Upswing but I’ll just share two of the themes here.

- Membership vs Sponsorship: During the “upswing” period, membership in social groups involved active engagement in the work being done in the community. For Churches, this meant members actively giving their time and energy to the community in a broad variety of ways. This created bridging relationships in the community and fostered programs that were responsive to the community, rather than being based on formal studies or academic approaches. This also exposed many people to leadership and social work for the first time, which lead to them launching their own programs, changing their career path, or running for public office. During the “downswing” period, the membership model drifted away from active involvement towards a model of financial sponsorship; social outreach increasingly became professionalized with experts doing the work following formal models. The authors note that this had many positive outcomes in program efficiency and effectiveness, but also had negative consequences which lead to a decrease in bridging relationships, less opportunities for transformative experiences, and less flexible community programs (increasingly driven by experts, consultants, studies, and formal models rather than direct community relationships).

- Collective vs. Individualistic Religion: During the “upswing” period, religious groups increasingly focused on the “we” rather than the “I” – people found their identity together, there was more of a focus on what do we do for each other and what do we do together rather than on individual sin or piety. The authors note that while this trend had many positive socioeconomic outcomes it has to be acknowledged that this lead to a strong conformist trend perhaps best exemplified by the stereotypes of the 1950s. This strong sense of conformity directly lead to the counter surge of individualism that gained momentum in the mid-1960s and continues to now. The authors argue that this individualistic trend dramatically affected Church in North America – pushing it away from the Social Gospel and towards a stronger focus more on individual experience. Many people opted out of organized religious entirely in favor of individualistic spirituality. The authors don’t comment on the spiritual aspects of this more individualistic approach but thoroughly document the negative impacts on the community due to the more inward religious focus.

There is a full chapter on the “downswing” so that’s too in-depth for me to write further about here. If you’re really interested in that I’d recommend the book but, again, be forewarned that it is a dense and data driven tome.

Alternatively, there’s a 2023 documentary on Putnam’s work on Netflix called Join or Die. This is focused on his book Bowling Alone, which was released in 2000, so it doesn’t offer the same historical perspective but does overlap with his theories on social capital.

Wow! Intense!