In November I traveled to Kratie province on a monitoring visit to the Rural Livelihoods and Social Cohesion in Interethnic Communities project. I was on my own this time – unlike our April 2022 visit – and met up with staff from our partner Cambodian Rural Development Team (CRDT).

The trip from Phnom Penh to Kratie town usually takes 7 to 8 hours one way by van or bus. The project sites are another 2 to 4 hours, depending on season and road conditions, from Kratie town.

I got some fried crickets with lemongrass, kafir lime leaves, and chilis for a snack along the way. A delicious, nutritious, and sustainable source of protein.

Our partner, CRDT, runs a number of ecotourism social enterprises in Kratie province. I stayed at one of them, the Le Tonlé Guesthouse, which is on the water front and has a great view of the Mekong river.

Having rice and pork for breakfast with Mr. Bo Ravuth, one of the staff at CRDT, before heading out into the countryside.

Our projects in Kratie province are in remote villages along the Mekong river, on islands in the Mekong, and in forested areas. So we have to take ferries, like this, to reach island communities.

The local ferries are always interesting. You never know what mix of people, animals, and goods will be on them. When I lived in Prey Veng I would sometimes travel with Cham people and their herds of goats. There were motos and bags of Pomelo fruit on this one. You also don’t know exactly when the ferries will arrive or depart. So there’s a lot of waiting by the river bank.

I started by attending a village savings group meeting at the Commune Center building in Damrae Village. I actually misheard and thought it was Domri village; ដំរី Domri means Elephant. But when I asked why they were the Elephant village they explained that it’s ដើម Dam [Tree] រ៉ា Rae [Type of Tree].

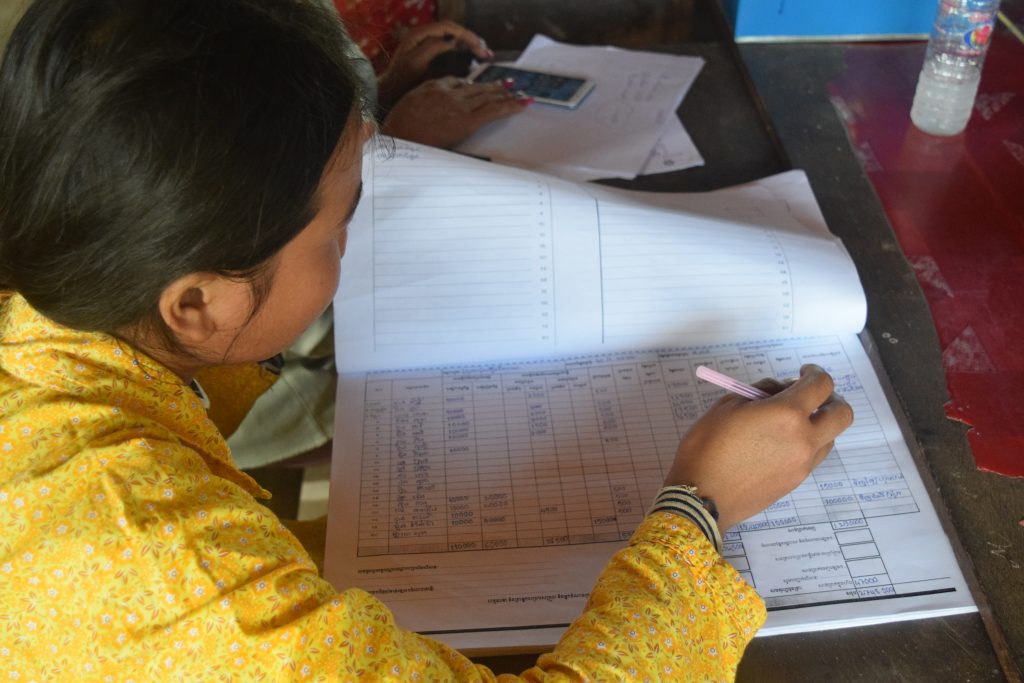

The group representative Hom Rattana writes entries into the ledger to track monthly membership dues, farmer loans, and repayment.

The Saving Group members are all classified by the Cambodian government as living below the national poverty line. Saving Groups members contribute 10,000 Riel (approximately $2.5 USD) a month to the fund which they can then borrow from in order to fund their farming activities. This model creates a self-sustaining revolving fund for poor farmers and provides a mechanism for the local community to collectively help farmers through difficult times. The villagers shared that banks and financial institutions do not give loans with good terms, instead forcing farmers into situations where they may need to use their land as collateral and risk losing their homes and livelihoods. The Village Saving Groups provide a sustainable community based alternative.

Then I visited several farms in Damrae village. Here I’m talking with Man Sokha, a member of the village savings group. Man Sokha has two children; an 11 year old and a 7 year old.

She has borrowed 200,000 riel ($50 USD) from the Village Savings Group to raise chickens and construct a climate resilient and disease resistant chicken shelter.

Climate change induced shifts in water patterns have resulted in broader spread of diseases. This is a broader topic that should have it’s own post but I’ll quickly list some of the ways that this occurs in Cambodia.

- Rainfall during the dry season enable certain causing fungi to spread more broadly throughout the year. Natural disasters and flooding increase the risk for mold and mildew.

- Disruption of seasonal weather patterns threatens wildlife habitants and food sources, pushing them into closer interaction with domestic animals and humans. This results in wildlife diseases jumping to domestic animals or humans.

- As temperatures increase, fungi adapt to the higher environmental temperatures…which creep closer and closer to tolerance to body temperature. This means that more diseases caused by fungi can affect humans and animals. As you might remember, I recently had two strains of mold fungi infecting my ear and I definitely would not recommend it.

- Nonseasonal flooding and rains result in the spread of water borne diseases. Extreme weather events can also overwhelm sanitation systems, releasing sewage into the environment. For example; there was a major outbreak of Typhoid in Phnom Penh last year.

- Disease carrying species like the Asian Tiger Mosquito already spread diseases like Dengue, Chikungunya, and Malaria. The heavy downpours of the rainy season and the long drought of the dry season both traditionally limited standing water. As mini-droughts occur during the rainy season and rainstorms occur during the dry season they leave standing water enabling mosquitos more opportunity to breed. The farmers I met with told me that the last few years have seem a dramatic increase in children suffering from mosquito borne diseases.

Man Sokha is also growing vegetables, including water spinach, and raising pigs following the techniques she learned from CRDT.

Man Sokha has just started to raise pigs. First she built the shelter according to CRDT’s recommendations.

Another farm that I visited belonged to Kong Seng. She has three children; the oldest is 12 and the youngest is 2 years old. Until recently she’s primarily been a rice farmer but is implementing the chicken raising and vegetable gardening techniques she learned from CRDT.

She borrowed 300,000 riel ($75 USD) from her village savings group to buy chickens and supplies and to construct the climate resilient chicken shelter. Seng is a member of a village savings group and producer group initiated by CRDT.

What’s a Producer Group?

MCC partners ODOV and CRDT both form producer groups on the village level. These are groups of farmers who are growing vegetables, chickens, fish, and so. They sell their produce collectively, which allows them to bargain as a group and get the best price for their produce instead of having the middleman make them compete with each other. They also purchase agricultural supplies – like chicken vaccines or seeds – collectively so that they can bargain for the best prices and save costs on transportation.

The producer groups also double as village savings groups or village banks. Each of the members contributes to the group fund and can borrow from it to fund their agricultural activities.

Because her chicken shelter is still under construction Kong Seng is keeping her chickens under her house for now.

While I was on the island I randomly ended up in a country wedding. Not just at but in the ceremomy; they actually asked me to cut the groom’s hair. Well, I said I didn’t want to mess up his hair and they said I could pretend. So I pretended to cut the groom’s hair.

After the wedding, which doubled as lunch, we traveled to Kampong Roteh village to meet with three producers/village saving groups. The meeting participants talked shared about their farming activities, their living conditions, and explained how climate change has been negatively impacting their livelihoods.

- In the past, the weather was seasonal and rainfall was reliable. Now the rainfall is inconsistent. In the rainy season, there might suddenly be a drought for two or three weeks which can ruin a rice paddy.

- In early dry season, there might be a sudden rain that soaks the rice waiting for harvest and threatens to ruin it with mold.

- There are also more cases of human and animal diseases. The villagers noted that they are seeing more and more tiger mosquitos (Aedes albopictus), even outside of the normal season. They thought this might be due to the non-seasonal rain. They also shared that more children than ever have been catching mosquito borne diseases like dengue, chikungunya, and malaria.

- The villagers noted that the weather has been hotter than usual and that there have been dangerous heat spikes. Several farmers shared stories of how extreme heat had killed their chickens.

- In the past, farmers would augment their income by traveling to work outside of the village during the dry season. They would return in time for planting and transplanting rice at the beginning of the rainy season. It is difficult to plan for this now due to the inconsistency of the weather.

One of the farmers I met, Kem Sopheat, was growing a tremendous amount of vegetables. When I asked her about it she explained that her oldest son, 18 years old, had left the island to work at a gold mine in a neighboring district. Mining is dangerous work that pays little and has no safety net in case of injury. Sopheat shared that recently some miners have died in accidents so she is very concerned about her son. She hopes that increasing her farming activities will allow her son to return home and make a safer living as a farmer.

I had good visits with several other farmers – it brought back memories of working in the countryside from 2006 to 2009 – but I think I’ll stop with those highlights. This post is already quite long. It did feel good to speak country Khmer again.

Excellent overview of both the variety of partners that you work with, as well as the unfortunate consequences of climate change… sadly, the lives of many in Cambodia are experiencing more first hand effects than most of us in the US. Keep up the good work, God bless!

Wow! Good work! Words of hope in a changing world!